The Market

Our market

Demand for Aggreko's services is created by events: our customers generally turn to us when something unusual happens which means they need power or temperature control quickly, or there is a requirement which is transitory. Events that stimulate demand range from the very large and infrequent to the small and recurrent.

Examples of high-value, infrequent events or situations we have worked on include:

- Large-scale power shortage – Bangladesh, Argentina and Indonesia.

- Major sporting occasions – Olympic Games, FIFA World Cup, Asian Games.

- Entertainment and broadcasting – Glastonbury.

- Natural disasters – Japanese tsunami in 2011, Nashville floods in 2010.

- Post-conflict re-construction – Congo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Examples of lower-value, more frequent events on which we might work are:

- An oil refinery needs additional cooling during the summer to maintain production throughput.

- A glass manufacturer suffers a breakdown in its plant and needs power while its own equipment is being repaired.

- A city centre needs chillers to create an ice-rink for the Christmas period.

How big is the market, and what is our market share?

Because we operate in very specific niches of the rental market – power, temperature control and, in North America only, oil-free compressed air – and across a very broad geography, it is very difficult to determine with any accuracy the size of our market. A complicating fact is that our own activities serve to create market demand – Bangladesh and Indonesia did not figure highly in our estimates of market size a few years ago, but they are now important customers as a result of our sales efforts. Furthermore, our market is event driven, and major events such as hurricanes in North America, the Olympic Games, or major droughts in Africa can influence market size in the short-term.

As there is no third-party research that exactly matches our business, we have to use a number of different approaches to estimate the size of the global market. All of our measurements of market size relate to rental revenue, as services revenues like fuel and freight are highly volatile and do not have any reflection on underlying market size.

For most OECD countries in which we operate, we use three techniques:

- Supply-side estimation. We use market intelligence to estimate the supply-side – i.e. how large our competitors are. This is notoriously inaccurate, as competitors often have much broader product ranges. It is extremely difficult to work out how much of their revenue comes specifically from generators and chillers, and how much from the many other lines of equipment they may offer.

- Demand-side estimation. In our Local business, our global IT system and a much sharper emphasis on sector-based marketing, are helping us to develop an improved understanding of our revenue by sector and customer. For our International Power Projects business, we have invested considerable effort in proprietary research with professional economists to develop models which forecast the supply of, and demand for, power.

- Third-party data, where it is available.

By triangulating these techniques, we develop an estimate of market size but the truth is that it is a guess, and probably not a very accurate one. In 2003, we did a great deal of work on market sizing, and came to the conclusion that the market was worth about £1.3 billion and was growing at about 5%. Since then, our own rental revenues have grown at a compound annual rate (CAGR) of 20%, which would imply either that our market share has grown improbably fast, that the original market size was wrong or that we under-estimated the growth-rate. In all probability, the truth is a mixture of all three factors. Our best guess is that the market in which we operate is now worth somewhere around £4 billion per year. As part of our 5 year strategy review in 2012, we are commissioning a series of studies to get a better estimate of the market size, which will be presented in next year's report.

Given our rental revenues of £1,042 million in 2011, a £4 billion market would imply an Aggreko worldwide share of sales of around 25%. Behind this lies enormous variation. In many developing countries, where the rental market is barely developed, and where we are called in to provide temporary utility power, we may represent 100% of the power rental market for the period of the project but none when it ends. In OECD countries, where the rental markets are better developed, our share of the market will be lower than the 25% we estimate for our global share of the market. However, in nearly all the major markets in which we operate, Aggreko is the largest or second-largest player.

What drives market growth in the Local business?

Growth in Aggreko's Local business is driven by three main factors:

- GDP – as an economy grows, so does demand for energy.

- Propensity to rent – how inclined people are to rent rather than buy. This is driven by issues such as the tax treatment of capital assets and the growing awareness and acceptance of outsourcing.

- Events – high-value/low-frequency events change the size of a market, although only temporarily. For example, the scale of the Japanese tsunami has led to a short-term surge in temporary power demand in the areas affected by the disaster; likewise, the FIFA World Cup in 2010 vastly increased the market for power rental in South Africa, but for 6 months only.

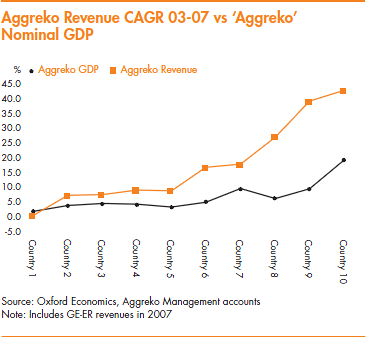

In seeking to understand the drivers of growth better, we have devised the concept of 'Aggreko GDP'; this is the GDP of a country weighted to account for Aggreko's sectoral mix of revenues. Typically, this means that we are weighted more towards manufacturing than, say, financial services. Over the past few years, we have observed that in countries where the growth rate of Aggreko GDP is below 5%, our revenues tend to grow at 2-3 percentage points faster than the rate of Aggreko GDP. In economies where Aggreko GDP growth is above 5%, we get an increasingly leveraged effect, with Aggreko sales growth far outpacing GDP growth. This is for a number of reasons but, most notably, simply that when economies are growing fast, customers want equipment quickly; they want high levels of service, and they want to focus on doing what they are good at, rather than owning large amounts of equipment.

The graph below plots this relationship between growth in Aggreko's revenues by country and growth in Aggreko nominal GDP between 2003 and 2007. We have not included 2008 – 2011 because the data for these years is polluted by the global recession during this period. We would also caution that these figures include the impact of the GE Energy Rentals acquisition in December 2006 which will exaggerate the underlying sales growth in some countries, but we feel that the trend they show is directionally correct.

Overall, in times of positive GDP growth, we estimate that the market addressed by our Local business for the short-term rental of power and temperature control is growing at some 2-3% above GDP in developed markets. So, if GDP grows at 3% on average over the cycle, our market should grow at about 5%. In countries with rates of nominal GDP growth that are above 5%, the market can grow much faster.

An obvious question is “so what happens in a downturn?” The experience of the last 2-3 years has been instructive but, before discussing it, we have to qualify the analysis by saying that all recessions are different and, just because our business behaved one way in the recession of 2008-2009, does not mean it will behave the same in the next one.

We started warning in early 2008 that we thought that demand and rates would weaken in our Local businesses in North America and Europe, but it was not until the second quarter of 2009 that we felt any impact, with demand weakening in almost every Local business. From this might come the tentative conclusion that our business is 'late-cycle'. Whether that will be true of all future recessions is uncertain, as there are no particular reasons we can think of which would explain why customers should seek to leave cutting back on our services until the recession is well underway. We also recovered from the recession extremely quickly; within a year our like-for-like volumes in the local business were growing again. The recovery was particularly sharp in North America. One might conclude from this that Aggreko is in the happy position of being late-cycle into a recession and early-cycle out of it. We would be very suspicious of such a golden scenario. We think, on balance, that a number of factors helped us: unlike many businesses, we trimmed our costs rather than hacked them and, above all, sought to keep our sales force in place, which meant that we were able to maintain relationships with customers through the downturn and were ready to serve them when they were ready to buy again; our global reach and presence in markets that barely felt the impact of the recession also helped us, as did our exposure to customers in sectors such as oil and gas and petrochemicals in which plant maintenance can be delayed a year or two, but, ultimately has to be done. We were also the beneficiaries of great good luck, in that 2010 was an 'annus mirabilis' in major events revenue, with the Vancouver Winter Olympics, the FIFA World Cup, and the Asian Games all occurring in the same year, generating some £87 million of revenue. This happy coincidence of three major events in a single year happens only once every 4 years.

During the period we really felt the recession in our Local business (Q2 2009 to Q1 2010), and we reduced rates to keep volumes up for the critical summer season. The power and temperature control businesses reacted very differently; power volumes were surprisingly stable, but temperature control volumes dropped by about 10%. For many of our customers, being without power is not an option, but going without extra cooling capacity may well be possible, particularly if industrial customers are not running their processes at full capacity. Rates fell for both power and temperature control during this period.

Our conclusion from this? It is that, in a recession, the Local business probably behaves the same way as it does when GDP is growing – i.e. volume shrinks at about twice the rate of Aggreko GDP, but there is then an additional impact of rate erosion which can be of the order of 5-10%.

What drives market growth in the International Power Projects business?

The factors which drive the growth of our International Power Projects business are different. The main trigger of demand is power cuts; when the lights go out in a country, people want power restored as quickly as possible. It is a perverse fact that people value power most when they are without it. We believe that in many parts of the world, and most particularly in many developing countries, there will be increasing numbers of power cuts, caused by a combination of burgeoning demand for power and inadequate investment in new capacity.

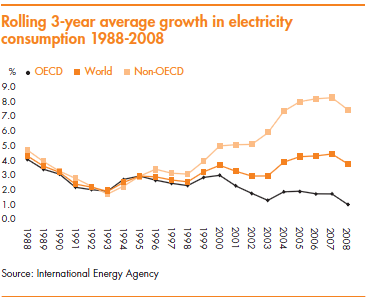

We believe that demand for power is going to grow much faster than is commonly believed; working with a leading group of professional economists at Oxford Economics, we have built a model which takes data on GDP and population growth, power consumption, and power generation capacity for 120 countries over the last 10 years. Using this historical data, it then projects future power demand based on forecasts of population and GDP growth. Our model predicts that world-wide demand for power will grow by around 4% per annum between 2007 and 2015, compared with forecasts by the International Energy Agency (IEA) of 2.6%. Our model reflects the sharp divergence between the growth in power consumption between OECD and non-OECD countries in recent years, as shown in the graph below. Poor countries are seeing demand for power increasing by over 7-8% per annum, whilst rich countries are growing at under 1-2% (see graph below).

The rapid growth in power consumption in developing countries is driven by industrialisation and by the growing number of consumers having access to devices which consume electricity, such as fridges, televisions and mobile phones. Between 2000 and 2015, we forecast that the number of people whose power consumption is growing faster than per-capita GDP will double, from 2.5 billion to over 5 billion (see graph below). The majority of these people live in developing countries, where investment in the acquisition of new generating capacity and maintenance of existing capacity has been far below the levels required to keep supply in line with demand.

.png)

To make this situation worse, by 2015, 25% of the world's installed power-generating capacity will be over 40 years old, which we believe is a reasonable proxy for the average life of a permanent power plant. The coming years will see the beginning of a replacement cycle during which a large part of existing power-plant construction capacity will be dedicated to replacing existing plants in North America and Europe, rather than building replacement or additional capacity in developing countries. The sums which need to be mobilised over the next 10 years to re-build the power distribution and generation capacity in North America and Europe are huge; in the UK alone, the regulator estimates that up to £200 billion will be required. This means that developing countries will have to compete for funds with developed countries, where investment risk is perceived to be far lower.

Our current models predict that the combination of these demand-side and supply-side factors will increase the world-wide shortfall of power generating capacity nearly 10-fold, from about 70 gigawatts (GW) in 2005 to around 600GW by 2015. Research which we are doing at the moment suggests that this figure may be high, and, over the coming year we will re-work and refine our models. The ultimate size of the shortfall will depend on both the rate of increase in demand, and the net additional generation and transmission capacity brought into production during the period. Even if the shortfall is lower than our current forecasts, it will still represent a level of global power shortage many times larger than today's. We are confident that such a level of power shortage will drive powerful growth over the medium and long term in demand for temporary power as countries struggle to keep the lights on.

Investors have been keen to understand what the impact of a recession might be on our International Power Projects business. In our 2008 Annual Report, we wrote “It is certainly likely that lower rates of percapita GDP growth will lead to slower rates of growth in demand for electricity in developing countries. However, we believe that, unless there is a prolonged economic catastrophe, the market for temporary power in developing countries will continue to grow.” Experience in the last three years has supported this hypothesis: growth in MW on rent during 2009 was 10%, down from 40% growth in 2008, but growth nevertheless; in 2010, we had record levels of orderintake and grew the MW on rent by 14%; in 2011 the MW on rent grew by 21%. Recent figures produced by the IEA suggest that consumption of electricity in non-OECD countries grew by 5.3% in 2008 – a recession notwithstanding. Another concern has been that recession might bring a bad-debt problem in International Power Projects, but this has not been our experience; the reasons some of our customers occasionally take time out from paying their bills tends to be more for organisational and political reasons, rather than macro-economic reasons.

We end this section with our customary warning: International Power Projects specialises in providing energy infrastructure in countries where political and commercial risk is high – sometimes very high – and the fact is that we do business where others fear to tread. To date, we have never had a material loss of equipment or receivables, but it is very likely that sooner or later one of our customers will misbehave. Our assets are at much greater risk of loss or impairment than they would be if they were sitting in the suburbs of London or New York or Singapore. We have extensive risk-mitigation procedures and techniques, but investors should regard the current level of returns in this business as being 'risk-unadjusted rates of return', because nobody has yet behaved badly enough to adjust them.